Our research group has bred corals able to better survive marine heatwaves. Our work, now published in Nature Communications, shows that it is possible to improve coral heat tolerance even within a single generation.

We did this using selective breeding: a technique used by humans for thousands of years to produce animals and plants with desirable characteristics. Selective breeding is how humans turned wolf-like dogs into St Bernards, chihuahuas and everything in between.

Now, selective breeding is being considered as a tool for nature conservation, particularly for coral reefs. The Coralassist Lab (of which we are part) and the Palau International Coral Reef Center have been working on coral heatwave survival specifically. Our latest results are the culmination of seven years’ work.

Marine heatwaves trigger mass coral bleaching and mortality, with 2023-2024 declared as the fourth global mass bleaching event. Assisted evolution methods — like selective breeding — aim to boost natural adaptation to buy time for corals under climate change.

Yet the improvement in heat tolerance in our selectively bred corals was modest compared to the intensity of marine heatwaves expected in the future. While selective breeding is feasible, it is likely not a panacea. We’ll still need to tackle the cause of mass coral bleaching by reducing greenhouse gas emissions in order to mitigate warming and give assisted evolution programmes time to take effect.

How to breed corals for heat tolerance

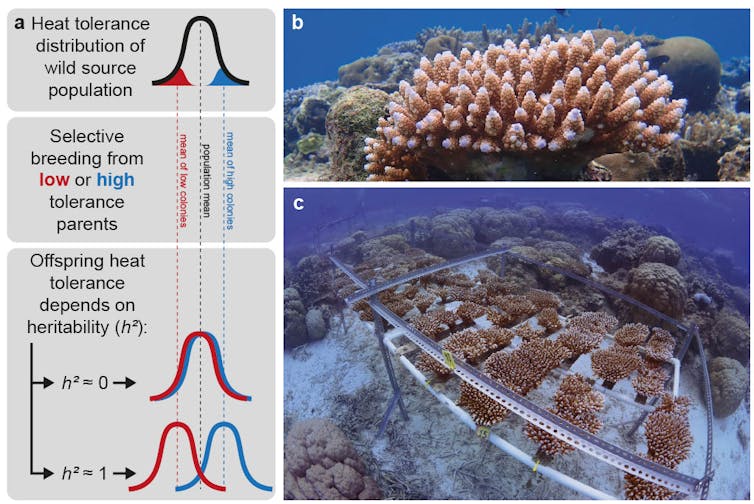

The first step was to determine the heat tolerance of many potential parent corals on the reef. Then, we chose specific individuals to breed two separate families of offspring, selected for either high or low heat tolerance. We reared these offspring for three to four years until they reached reproductive maturity, and then tested their heat tolerance.

Jesse Alpert

We conducted selective breeding trials for two different traits, either the tolerance to a short, intense heat exposure (temperatures 3.5°C above normal for ten days) or a less intense but long-term exposure more typical of natural marine heatwaves (2.5°C above average for a month). This enabled us to estimate the heritability of each trait, the response to selective breeding, and whether both traits have a shared genetic basis.

Selecting parents for high- rather than low-heat tolerance enhanced the tolerance of their adult offspring for both traits tested.

Coralassist lab

Heritability was roughly 0.2 to 0.3 on a scale of 0 to 1, which means about a quarter of the variability in offspring heat tolerance was due to genes passed from their parents. In other words, these traits have a substantial genetic basis on which natural and artificial selection can act.

We measure cumulative heat stress and tolerance in terms of degree-heating weeks (°C-weeks), which reflects both how hot it gets and for how long. Given the trait variability identified in these particular corals, heat tolerance could in theory be enhanced by about 1°C-week within one generation.

However, even this level of enhancement may not be enough to keep pace with ever more intense heatwaves. Depending on climate action, the intensity of heatwaves is expected to rise in the coming decades by around 3°C-weeks per decade, faster than the enhancement achieved in our study.

Interestingly, corals selectively bred for high- rather than low, short-stress tolerance were no better at surviving the long heat stress exposure. With no genetic correlation detected, it is plausible that these traits are driven by independent sets of genes, and corals that are good at surviving the short sharp heat stress aren’t necessarily the best at surviving longer term marine heatwaves.

This would have important implications, as work like this would benefit from cheap and rapid tests that can effectively identify heat tolerant colonies for breeding. However, if these tests can’t predict which coral colonies will survive month-long heatwaves, it presents a serious challenge.

Liam Lachs

Scaling up selective breeding

Since it is possible to selectively breed corals for increased heat tolerance, the next step is to conduct large-scale trials in the wild. This will likely require considerable numbers of selectively bred corals to be deployed, perhaps by directly seeding coral larvae on reefs, or planting corals reared in an aquaculture facility.

For this to work, outplanted corals must become reproductive themselves and contribute to the wild population gene pool. Doing this at very large scales will be challenging, but it may not be necessary to replenish the coral coverage of large areas.

Instead, it may be sufficient to create a network of fewer strategically located larval production hubs, containing selectively bred corals at high densities to maximise fertilisation success. These hubs would serve to seed other reefs and could provide further broodstock for targeted actions.

A lot more research and development is still needed, with many critical questions remaining unanswered. How many corals need to be outplanted to have the desired effect? Can we ensure there are no trade-offs that could compromise populations (evidence so far suggests this is not a large risk)? How can we avoid dilution of selected traits once added to the wild? How can we maximise responses to selection?

Given the pace of ocean warming, optimisation and implementation of assisted evolution will need to happen soon for them to have a chance at success, even if only on small scales. Above all, the survival of coral reefs still depends on urgent climate action.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get our award-winning weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 35,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.